On April 14, Souspilnist Foundation launched the project “Antithesis. Talking at the shelter about what matters.” It is a unique video format of conversations with Ukraine’s leading intellectuals, authoritative experts, and public opinion leaders.

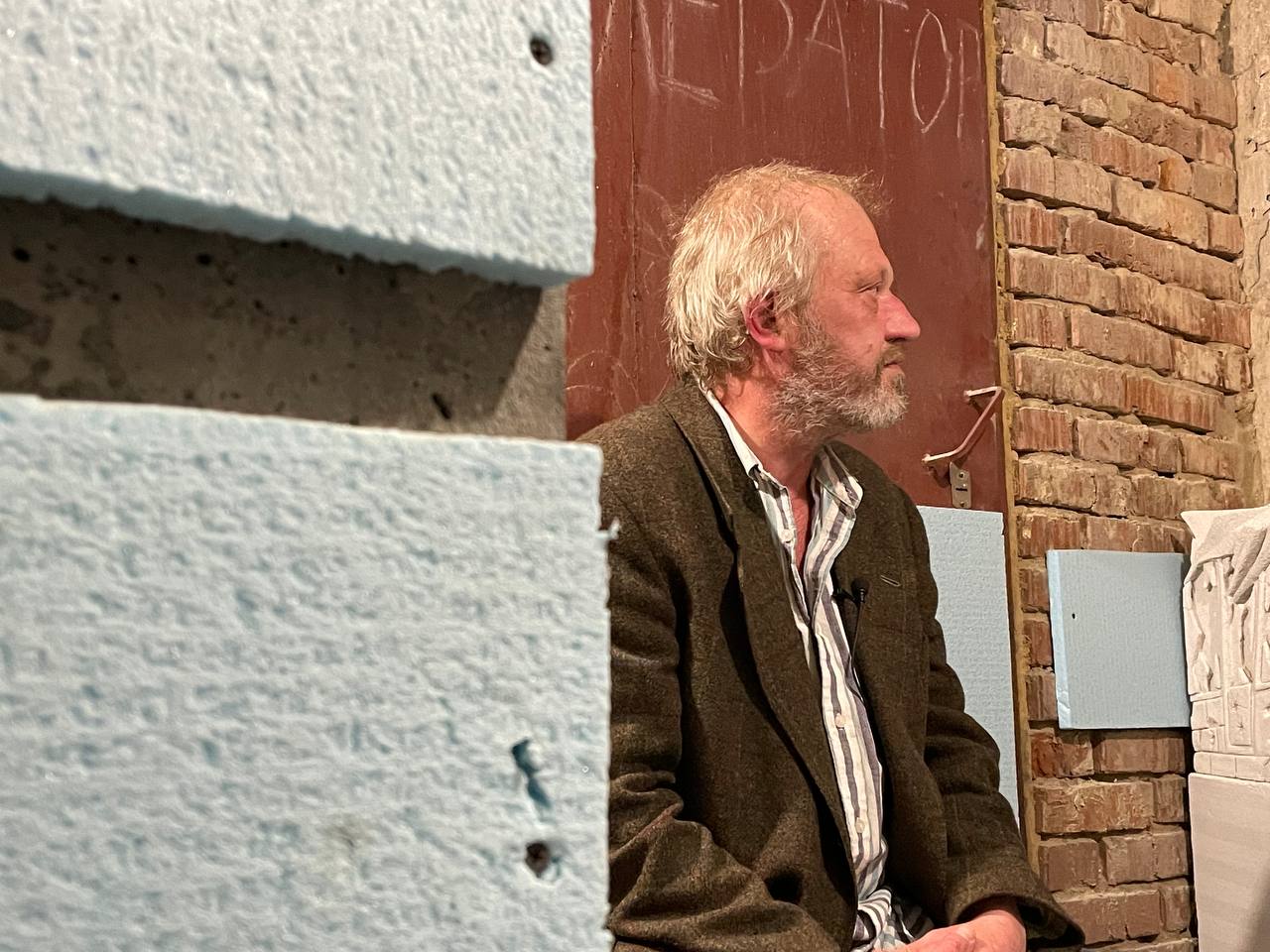

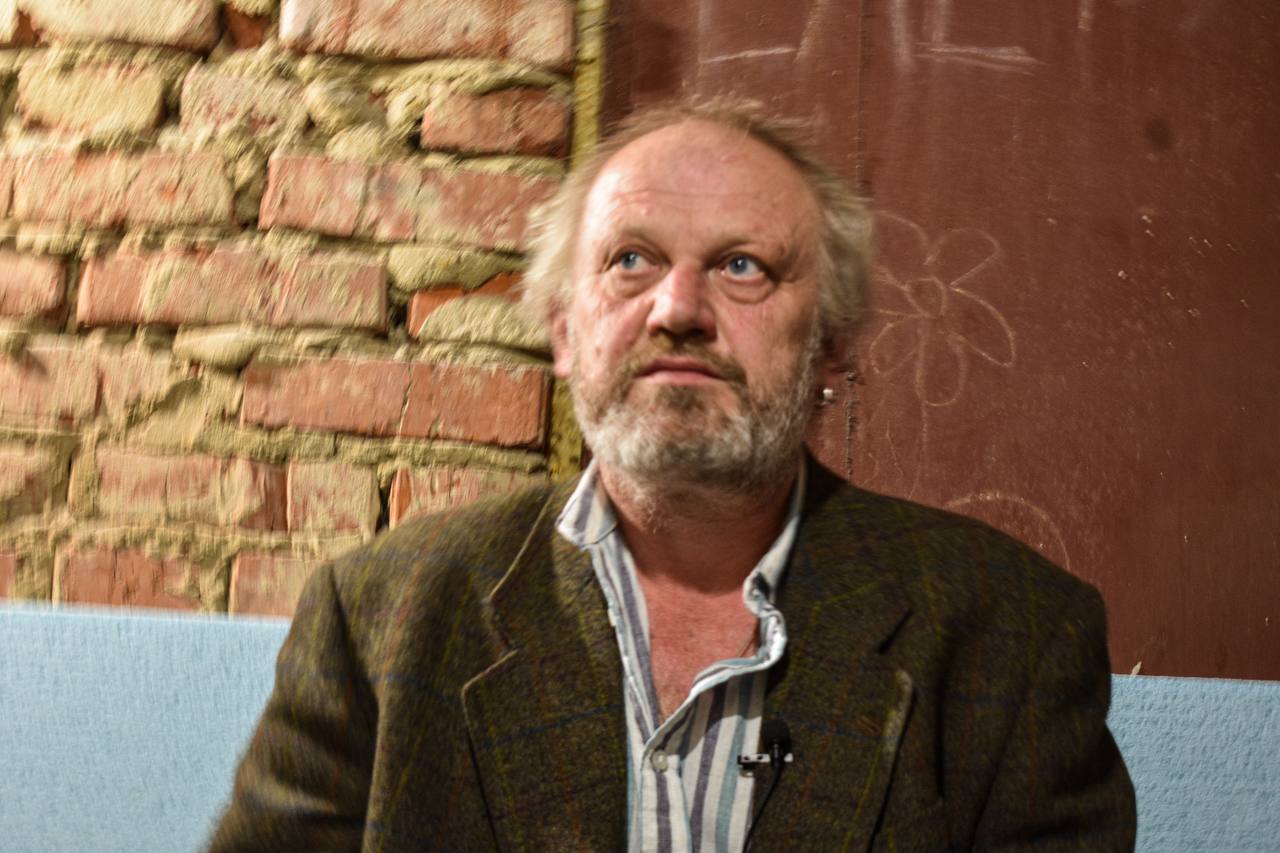

Our first guest was Taras Prokhasko, a modern Ukrainian novelist. Ivan Tsyperdiuk and Ira Mykhailchuk hosted the conversation.

Text in Ukrainian: Darya Khrystyniuk.

Interpreter: Taras Omelchenko.

Ivan Tsyperdiuk: Even though we are in the shelter now, overall, considering the one-and-a-half months of the war, what’s a safe place to you and your family? Of course, if you go to the shelter or have some other hiding place. So what’s a shelter mentally or spiritually?

Taras Prohhasko: I have a strange situation regarding safety. We’ve tried once or twice, with a small child, mother, and woman to go into a root cellar somewhere. We’d even built a shelter together on Kurbas Street. If you’re there, that’s a place to run to. But you know how that works: until you hear the sound of explosions… I’ve noticed that over time, and because no civilian objects have even been hit in Frankivsk, nearly everyone feels relieved from this…

ITs: …fever, this fever. When we could sit in the hallway because everyone was overwhelmed by a panic attack.

TP: Right, although I keep my bed away from the window. At least so that if the glass breaks, then…

ITs: Do you close your curtains to avoid the flying glass fragments?

TP: Yes, of course.

ITs: You see, I do that too.

TP: We could immediately spot those who’d come from Kyiv. We could spot them in the streets because they immediately ran to hide somewhere upon hearing the sirens. But now there are only a few of them in Frankivsk, it seems. It’s good that things look OK now. Not the most tragic situation, as it turns out.

ITs: Your apartment is next door, within a hundred meters, and it’s seen more than one war. You family, too, has always been on our Ukrainian side, actively involved in these wars. What’s this next Russian-Ukrainian war like to you and your family?

TP: It’s by no means a surprise to me. This looks a continuation of a specific process of the Ukrainian liberation idea’s development for me.

For many years, I’ve suffered that my country somehow deviated from the Ukrainian ideals that I and my environment, my generation, had dreamed of, at least when Ukraine became independent.

I wasn’t pleased with one thing or another. That is, it was never a complete delight. But now, it seems to me the moment has come when it’s possible to dedicate yourself entirely to this country and this idea, without any doubt whether it’s worth it or not, whether it’s my business or not. That is, I hope we’re having a peak moment now.

ITs: We’re not military strategists, so I’ll ask you about what’s closest to us, and especially to you as a writer. What impresses you most about the information war russia is waging simultaneously with the military campaign? What are your most striking moments as an artist? And what about russia’s fake stories that affect you and virtually every Ukrainian?

TP: Unfortunately, it doesn’t affect me in any way because I grew up with it. I spent my childhood and school years in the Soviet Union. I’m aware of all this rhetoric, fake stories, all this way of talking when you say one thing but mean something else, and when you keep on denying things. That’s right, episodes and figures change but it’s all like the Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

Peter Pomerantsev has said: “Nothing is true and everything is possible” (his book’s title).

In this sense, I especially liked one of Surkov’s ignored articles. On February 15, he wrote an article that was ridiculed because it was a mishmash of geopolitics and physical concepts (entropy, chaos). But I thought this was one of the best pieces for recognizing the actual level of cynicism and intellectual wackiness of the russian idea.

ITs: I thought you were resilient to fake news and information warfare. Your son Markian, also a writer, writes excellent posts on Facebook, where you’ve never been present. He shows what the muscovites did wrong here and there. It debunks stuff very well, in the best sense. That’s why the Prokhaskis don’t walk past the information warfare, you know.

TP: I mean, all this no longer affects me. As they’d put it a few months ago: I’ve gotten over it. Maybe even twice. So, I’m fully vaccinated against everything they say or do.

ITs: I constantly recall your columns on Zbruch. Ten or several hundred have appeared there in recent years. There are many memories of your army years. You were in direct contact with the russians, looking into the depths of this mysterious russian soul and these people’s behavior. From the standpoint of your knowledge of russians (not only as a writer who’s read Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, etc., because it was interesting to know their writing), how come it took them just a few years to degrade such a vast country and large nation to the point where they became a cattle herd?

TP: That’s what we’re talking about: this war is not a surprise, just like the russian nature. Unfortunately, it’s nothing new. It’s only the so-called “reaction and thaw,” as my Russian literature teacher put it, or something along those lines. Some fermentation. But, as another Russian author, Lenin, put it speaking about some early revolutionaries, “they are terribly far from the people.” Therefore, all these russian “thaws” are terribly far from the people.

ITs: Maybe they’re just freaks for the most part? Can we put it that way?

TP: How did the nobles differ from the ordinary people (in France, Germany, in ancient times)? Nobles know how to control themselves and keep their tempers in check. Of course, they can freak out and cut someone. But they understand what is acceptable and what isn’t. I’ve noticed that russians have a low threshold of unacceptability. It’s easy for them to do unacceptable things, and most importantly, they aren’t ashamed of it.

ITs: In the Ukrainian environment, there’s an intense debate about their interpretation of God and God’s laws being utterly different from ours. It’s a war out there again, and they say it is anti-god. Anything divine they ever had has turned into satanic, although they continue talking about God.

Perhaps that’s what doesn’t allow the russian people to stop to find moral foundations? They merely have nothing to rely on, and Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, I don’t think any russian reads that a lot.

TP: After all, reading Dostoevsky and Tolstoy – I wouldn’t say it’s pleasant for russians. If the readers are thoughtful, they should see that the so-called great russian literature is a terrible, devastating critique of russian man. That is, the entire great russian literature somehow weirdly has the same thing as Surkov. All the beauty of russian literature is to show how disgusting this life is.

ITs: …It’s a kind of continual degrading.

TP: And that’s good. Life is not valued at all in the russian social contract. We’ve always known it, and it’s even more so now. There’s also this constant superiority of the most degrading kind. Even when oppressed or degraded, they feel superior, the middle finger in their pocket.

They have no faith in any authority or ideals. It’s a tradition, and it keeps being handed down.

I’ll say this for the bomb shelter: russian literature or no russian literature, but I know that there’s even such a category as “russian porn” within international content, right? That is, it stands alone for a reason. This is a beautiful illustration of this “acceptable-unacceptable” threshold. Valuing life and valuing other things, and this supremacy. It’s like there’s a constant need to degrade everything somehow.

Look also at all russian conquests: they’re destroying everything. Wherever they come, all those nice countries, they destroy everything. Even with the socialist Czech Republic and Poland they occupied, look what they did. That is, being good is no use. It’s got to be spoiled anyway. Again, the characteristic gesture everyone’s been long talking about. And now we’ve got evidence of these piles of poop again.

ITs: …On the table, in the sink somewhere. And this is done on purpose.

TP: In fact, that’s a way to “raise” someone in better shape to your level of lowliness. Degrading others to lowliness is the greatness or victory.

ITs: Anyway, we’re in the shelter, and social networks are active.

Ira Mykhalchuk: Right, we have a question from the user Tatiana. She asks: what better options would you recommend instead of russian literature? Something to raise your children on? What Ukrainian literature about World War II (fiction) would you recommend?

TP: I don’t object to russian literature, and I wouldn’t want to. I believe it should be there. I’m just saying what it is about and what it says. I’m certainly not against reading it because it’s our neighbor, our enemy. You must know your enemy or neighbor. And I hardly ever read Ukrainian literature about World War II because I grew up not reading any Soviet literature.

I had several decades of my life when I didn’t read Soviet literature.

I’m sorry, Tetiana. I can’t say right off the bat; I think it’s a responsibility. I would advise you to read Czechs, e.g., Hrabal’s “Closely Watched Trains,” or at least watch Menzel’s film to understand the war as a metaphor for life.

ITs: And how do you think our modern literature will reflect on this ongoing war?

TP: I think now they’ll pay less attention to semi-documentary literature about army life, field conditions, or hostilities. We’ve had enough of that already. Some authors wrote from the battlefield. It was an excellent and important step because those were the people not far removed from it.

ITs: Soldiers, people not engaged in literature, culture. But they wrote about what they saw. It was going directly: a flow of consciousness and experiences.

TP: Now, if all goes well (although what’s good for society isn’t always so for literature, on the contrary, good literature occurs even under the worst conditions), the time has come for novels to appear where fighting and suffering like bomb shelters, shellings, etc. will be on the periphery of things. They’ll be there not as an element but as something to help grasp the meaning.

ITs: Are you saying there’ll be human stories?

TP: Right, human stories containing the questions: what for, what, how, and where? Including novels immersed in older stories.

Although I know that the readerships’ recovery after the war occurs when writers come up with adventure pieces about the war and when all these heroic things appear instead of films full of pathos or tragic films.

IM: Alina has a question: How do you think we must protect ourselves from russian manipulation and the desire to “reformat” Ukrainians’ brains?

TP: As a former biologist, I’d put it this way: you should start by not reading or looking at russian information. There are times when it’s better to have less information containing forced or justified censorship than to take the risk and allow yourself to be seduced until you have developed immunity. The russians are good at such things, at degrading people, at pulling people down.

ITs: Tempting evil.

TP: Yes, seductive evil. Many people want to believe that those around them are worse than they seem. Russian information is subtly working on this. There are all sorts, but they expose them (people) so much and in such a warped form that you get this pathetic desire to say: “I knew it, everything can’t be as good as they say it is,” or “So much money’s been stolen,” – and there you go.

One aspect of psychology dealing with changes in consciousness has such a thing as basic perinatal matrices. People with a specific mindset, with specific matrix, the mind settings or something, pick up facts like through a meat grinder from the entire world riches to fit within their matrices. And if someone has mistrust or fear, only the things meeting their matrix’s needs, i.e., suspicions, will get magnetized to them from the whole variety of things.

ITs: In fact, that’s the recipe you mentioned initially: don’t read their information, don’t watch, don’t let yourself be “tempted by the devil,” don’t give him a chance.

TP: Importantly, you shouldn’t think: “I’ll analyze it now” because there’s always this particular puzzle waiting for each analyst to lure them into their version.

ITs: Taras, do you plan on writing something about these times in the future? Not necessarily about the war, but to think about these times through your texts.

TP: Let’s see how that works out. I’ve got so many debts to myself, different people, and the times I’ve wanted to write about for a long time. But, of course, this won’t go down. I don’t believe there are any pure, purified periods. It’s all inside every person who’s survived these times, and it’s growing. Even if you look at the color of a tree trunk, you’ll see that the trunk is composed of different fragments, yet it holds the tree together.

ITs: I have to ask you this: what will you do on the day of our victory?

TP: I’ll be rejoicing, having fun, and thinking of those scattered in different directions and worlds, including somewhere in entirely different worlds. But I’ll also know that you need to breathe well during this time, like in boxing – a one-minute break between the rounds. You must use the time to wave a towel, change your mouthguard, and pour water. Because, as Kant, or someone else, said, “once is more than once.” This is not the end.

ITs: Of course, this is not the end. There’ll be another stage, the next one.

TP: I do very much hope that this relative peace lasts long enough for the generations of children who’ve been affected and traumatized by the war to get rid of that impression at least a little to see that the war is not forever. No matter how much it hurts, especially for children, it’s possible to grow up and extend using various efforts and the help of others. I’ve seen a generation that lived and grew up in some peace and ease. But, as the poets say, they’ve already been charred by the war.

My biggest dream is to give them [children] another 10-15-20 years, so their formation is not entirely associated with the war.

ITs: Thank you for coming. I can imagine how many people are currently in shelters in Ukraine, but for all of us, this has been a meaningful conversation with you.

TP: I am very grateful because one of the wartime problems is the lack of opportunity to speak out, think out loud, or say something to yourself. So you’re saving me, too.

You can watch the program on Souspilnist Foundation’s Facebook page and our partner media platforms: KURS, Reporter, and TRK RAI.